|

To print these notes, use the PDF version. |

|

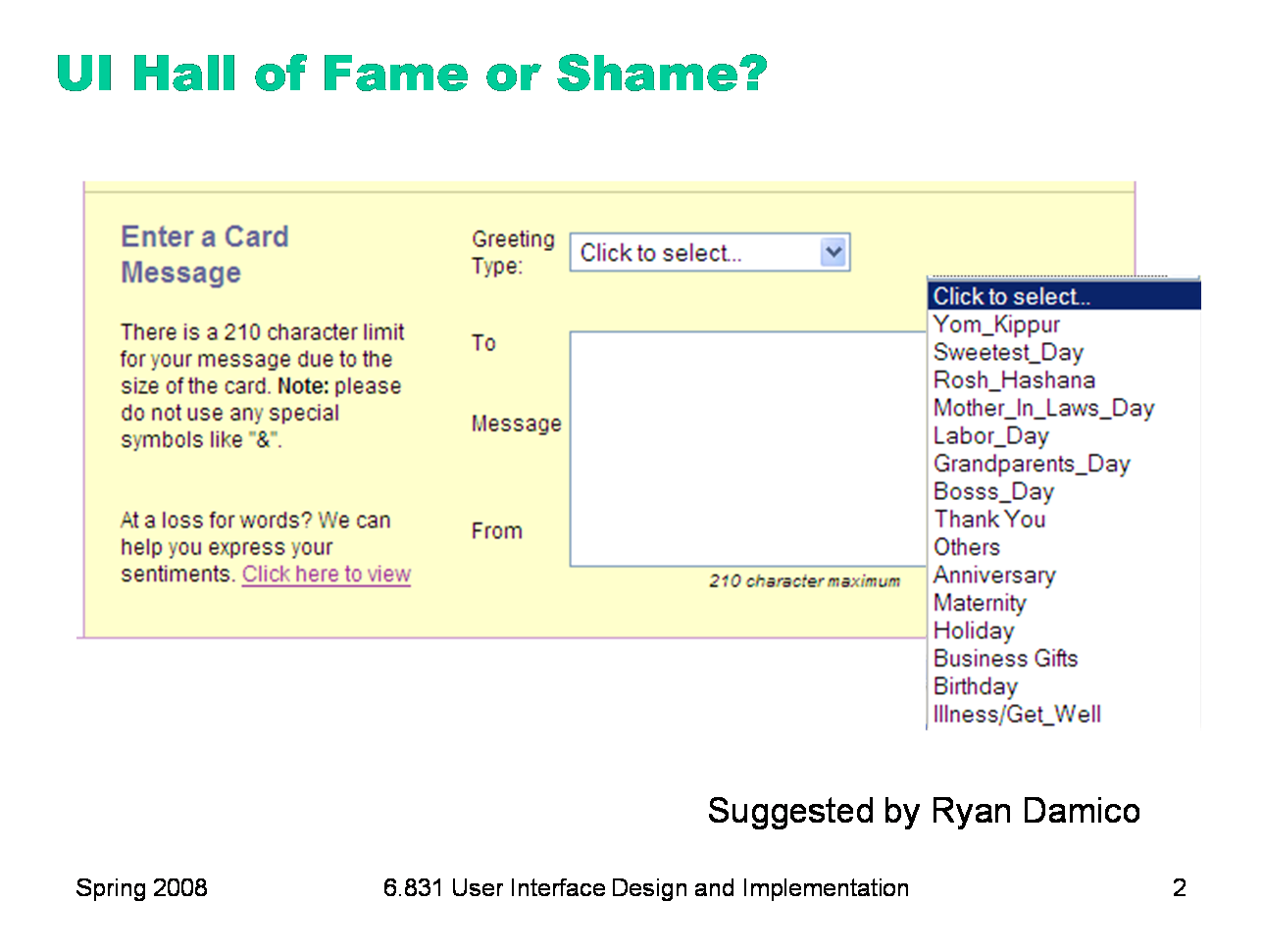

Today’s candidate for the Hall of Shame is this entry form from the 1800Flowers web site. The purpose of the form is to enter a message for a greeting card that will accompany a delivered flower arrangement. (So you can see the whole interface, I’ve moved the Greeting Type drop-down menu to the right. In the real interface, it appears where you’d expect, right under the Greeting Type drop-down box.) How does this interface fare with respect to: - user control and freedom - visibility - consistency - speaking the user’s language

|

|

In this lecture, we’ll talk about user testing: putting an interface in front of real users. There are several kinds of user testing, but all of them by definition involve human beings, who are thinking, breathing individuals with rights and feelings. When we enlist the assistance of real people in interface testing, we take on some special responsibilities. So first we’ll talk about the ethics of user testing, which apply regardless of what kind of user test you’re doing. The rest of the lecture will focus on one particular kind of user test: formative evaluation, which is a user test performed during iterative design with the goal of finding usability problems to fix on the next design iteration.

|

|

Here are three common kinds of user tests. You’ll be doing a formative evaluation with your paper prototypes. The purpose of formative evaluation is finding usability problems in order to fix them in the next design iteration. Formative evaluation doesn’t need a full working implementation, but can be done on a variety of prototypes. This kind of user test is usually done in an environment that’s under your control, like an office or a usability lab. You also choose the tasks given to users, which are generally realistic (drawn from task analysis, which is based on observation) but nevertheless fake. The results of formative evaluation are largely qualitative observations, usually a list of usability problems. Note that Prototype Testing Day is not the best way to do formative evaluation: first, because your classmates are probably not representative of your target user population; and second, because we have artificial time constraints that raised the pressure on users and experimenters, prevent using substantial tasks, and don’t allow for much debriefing or discussion after the test. Better user tests would use representative users and be more relaxed (unless time pressure is a key attribute of the actual working context of your interface, in which case maybe you’d want to try to simulate those conditions intentionally). A key problem with formative evaluation is that you have to control too much. Running a test in a lab environment on tasks of your invention may not tell you enough about how well your interface will work in a real context on real tasks. A field study can answer these questions, by actually deploying a working implementation to real users, and then going out to the users’ real environment and observing how they use it. We won’t say much about field studies in this class. A third kind of user test is a controlled experiment, whose goal is to test a quantifiable hypothesis about one or more interfaces. Controlled experiments happen under carefully controlled conditions using carefully-designed tasks — often more carefully chosen than formative evaluation tasks. Hypotheses can only be tested by quantitative measurements of usability, like time elapsed, number of errors, or subjective ratings. We’ll talk about how to design controlled experiments in a later lecture.

|

|

Let’s start by talking about some issues that are relevant to all kinds of user testing: ethics. Human subjects have been horribly abused in the name of science over the past century. Here are some of the most egregious cases: In Nazi concentration camps (1940-1945), doctors used prisoners of war, political prisoners, and Jews as human guinea pigs for horrific experiments. Some experiments tested the limits of human endurance in extreme cold, low pressures, or exposure. Other experiments intentionally infected people with massive doses of pathogens, such as typhus; others tested new chemical weapons or new medical procedures. Thousands of people were killed by these experiments; they were criminal, on a massive scale. In the Tuskegee Institute syphilis study (1932-1972), the US government studied the effects of untreated syphilis in black men in the rural South. In exchange for their participation in the study, the men were given free health examinations. But they weren’t told that they had syphilis, or that the disease was potentially fatal. Nor were they given treatment for the disease, even as proven, effective treatments like penicillin became available. Out of 339 men studied, 28 died directly of syphilis, 100 of related complications. 40 wives were infected, and 19 children were born with congenital syphilis. In the 1940s and 1950s, MIT researchers cooperated with the Fernald School for mentally disabled children in Waverly, Massachusetts to gave radioactive isotopes to some of the children in their milk and cereal, to study how the isotopes were taken up by the body. Permission letters were obtained from their parents, but neither parents nor children were warned that radioactive materials were being used. In the 1950s, a famous study done at Yale told subjects to give painful electric shocks to another person. The shocks weren’t real, and the person they were shocking was just an actor. But subjects weren’t told that fact in advance, and many subjects were genuinely traumatized by the experience: sweating, trembling, stuttering. These abuses have led to several reforms. The Nazi-era experiments led to the Nuremberg Code, an international agreement on the rights of human subjects. The Tuskegee study drove the US government to take steps to ensure that all federally-funded institutions follow ethical practices in their use of human subjects. In particular, every experiment involving human subjects must be reviewed and approved by an ethics committee, usually called an institutional review board. MIT’s review board is called COUHES.

|

|

Experiments involving medical treatments or electric shocks are one thing. But what’s so dangerous about a computer interface? Hopefully, nothing — most user testing has minimal physical or psychological risk to the user. But user testing does put psychological pressure on the user. The user sits in the spotlight, asked to perform unfamiliar tasks on an unfamiliar (and possibly bad!) interface, in front of an audience of strangers (at least one experimenter, possibly a roomful of observers, and possibly a video camera). It’s natural to feel some performance anxiety, or stage fright. “Am I doing it right? Do these people think I’m dumb for not getting it?” A user may regard the test as a psychology test, or more to the point, an IQ test. They may be worried about getting a bad score. Their self-esteem may suffer, particularly if they blame problems they have on themselves, rather than on the user interface. A programmer with an ironclad ego may scoff at such concerns, but these pressures are real. Jared Spool, a usability consultant, tells a story about the time he saw a user cry during a user test. It came about from an accumulation of mistakes on the part of the experimenters: 1. the originally-scheduled user didn’t show up, so they just pulled an employee out of the hallway to do the test; 2. it happened to be her first day on the job; 3. they didn’t tell her what the session was about; 4. she not only knew nothing about the interface to be tested (which is fine and good), but also nothing about the domain — she wasn’t in the target user population at all; 5. the observers in the room hadn’t been told how to behave (i.e., shut up); 6. one of those observers was her boss; 7. the tasks hadn’t been pilot tested, and the first one was actually impossible. When she started struggling with the first task, everybody in the room realized how stupid the task was, and burst out laughing — at their own stupidity, not hers. But she thought they were laughing at her, and she burst into tears. (story from Carolyn Snyder, Paper Prototyping)

|

|

The basic rule for user testing ethics is respect for the user as a intelligent person with free will and feelings. We can show respect for the user in 5 ways: · Respecting their time by not wasting it. Prepare as much as you can in advance, and don’t make the user jump through hoops that you aren’t actually testing. Don’t make them install the software or load the test files, for example, unless your test is supposed to measure the usability of the installation process or file-loading process. · Do everything you can to make the user comfortable, in order to offset the psychological pressures of a user test. · Give the user as much information about the test as they need or want to know, as long as the information doesn’t bias the test. Don’t hide things from them unnecessarily. · Preserve the user’s privacy to the maximum degree. Don’t report their performance on the user test in a way that allows the user to be personally identified. · The user is always in control, not in the sense that they’re running the user test and deciding what to do next, but in the sense that the final decision of whether or not to participate remains theirs, throughout the experiment. Just because they’ve signed a consent form, or sat down in the room with you, doesn’t mean that they’ve committed to the entire test. A user has the right to give up the test and leave at any time, no matter how inconvenient it may be for you.

|

|

Let’s look at what you should do before, during, and after a user test to ensure that you’re treating users with respect. Long before your first user shows up, you should pilot-test your entire test: all questionnaires, briefings, tutorials, and tasks. Pilot testing means you get a few people (usually your colleagues) to act as users in a full-dress rehearsal of the user test. Pilot testing is essential for simplifying and working the bugs out of your test materials and procedures. It gives you a chance to eliminate wasted time, streamline parts of the test, fix confusing briefings or training materials, and discover impossible or pointless tasks. It also gives you a chance to practice your role as an experimenter. Pilot testing is essential for every user test. When a user shows up, you should brief them first, introducing the purpose of the application and the purpose of the test. To make the user comfortable, you should also say the following things (in some form): ·“Keep in mind that we’re testing the computer system. We’re not testing you.” (comfort) ·“The system is likely to have problems in it that make it hard to use. We need your help to find those problems.” (comfort) ·“Your test results will be completely confidential.” (privacy) ·“You can stop the test and leave at any time.” (control) You should also inform the user if the test will be audiotaped, videotaped, or watched by hidden observers. Any observers actually present in the room should be introduced to the user. At the end of the briefing, you should ask “Do you have any questions I can answer before we begin?” Try to answer any questions the user has. Sometimes a user will ask a question that may bias the experiment: for example, “what does that button do?” You should explain why you can’t answer that question, and promise to answer it after the test is over.

|

|

During the test, arrange the testing environment to make the user comfortable. Keep the atmosphere calm, relaxed, and free of distractions. (We failed on all three counts at Prototype Testing Day!) If the testing session is long, give the user bathroom, water, or coffee breaks, or just a chance to stand up and stretch. Don’t act disappointed when the user runs into difficulty, because the user will feel it as disappointment in their performance, not in the user interface. Don’t overwhelm the user with work. Give them only one task at a time. Ideally, the first task should be an easy warmup task, to give the user an early success experience. That will bolster their courage (and yours) to get them through the harder tasks that will discover more usability problems. Answer the user’s questions as long as they don’t bias the test. Keep the user in control. If they get tired of a task, let them give up on it and go on to another. If they want to quit the test, pay them and let them go.

|

|

After the test is over, thank the user for their help and tell them how they’ve helped. It’s easy to be open with information at this point, so do so. Later, if you disseminate data from the user test, don’t publish it in a way that allows users to be individually identified. Certainly, avoid using their names. If you collected video or audio records of the user test, don’t show them outside your development group without explicit written permission from the user.

|

|

OK, we’ve seen some ethical rules that apply to running any kind of user test. Now let’s look in particular at how to do formative evaluation. You’ve already done one formative evaluation test already, using your paper prototypes. So you know the basic steps already: (1) find some representative users; (2) give each user some representative tasks; and (3) watch the user do the tasks.

|

|

There are three roles in a formative evaluation test: a user, a facilitator, and some observers.

|

|

The user’s primary role is to perform the tasks using the interface. While the user is actually doing this, however, they should also be trying to think aloud: verbalizing what they’re thinking as they use the interface. Encourage the user to say things like “OK, now I’m looking for the place to set the font size, usually it’s on the toolbar, nope, hmm, maybe the Format menu…” Thinking aloud gives you (the observer) a window into their thought processes, so you can understand what they’re trying to do and what they expect. Unfortunately, thinking aloud feels strange for most people. It can alter the user’s behavior, making the user more deliberate and careful, and sometimes disrupting their concentration. Conversely, when a task gets hard and the user gets absorbed in it, they may go mute, forgetting to think aloud. One of the facilitator’s roles is to prod the user into thinking aloud. One solution to the problems of think-aloud is constructive interaction, in which two users work on the tasks together (using a single computer). Two users are more likely to converse naturally with each other, explaining how they think it works and what they’re thinking about trying. Constructive interaction requires twice as many users, however, and may be adversely affected by social dynamics (e.g., a pushy user who hogs the keyboard). But it’s nearly as commonly used in industry as single-user testing.

|

|

The facilitator (also called the experimenter) is the leader of the user test. The facilitator does the briefing, gives tasks to the user, and generally serves as the voice of the development team throughout the test. (Other developers may be observing the test, but should generally keep their mouths shut.) One of the facilitator’s key jobs is to coax the user to think aloud, usually by asking general questions. The facilitator may also move the session along. If the user is totally stuck on a task, the facilitator may progressively provide more help, e.g. “Do you see anything that might help you?”, and then “What do you think that button does?” Only do this if you’ve already recorded the usability problem, and it seems unlikely that the user will get out of the tar pit themselves, and they need to get unstuck in order to get on to another part of the task that you want to test. Keep in mind that once you explain something, you lose the chance to find out what the user would have done by themselves.

|

|

While the user is thinking aloud, and the facilitator is coaching the think-aloud, any observers in the room should be doing the opposite: keeping quiet. Don’t offer any help, don’t attempt to explain the interface. Just sit on your hands, bite your tongue, and watch. You’re trying to get a glimpse of how a typical user will interact with the interface. Since a typical user won’t have the system’s designer sitting next to them, you have to minimize your effect on the situation. It may be very hard for you to sit and watch someone struggle with a task, when the solution seems so obvious to you, but that’s how you learn the usability problems in your interface. Keep yourself busy by taking a lot of notes. What should you take notes about? As much as you can, but focus particularly on critical incidents, which are moments that strongly affect usability, either in task performance (efficiency or error rate) or in the user’s satisfaction. Most critical incidents are negative. Pressing the wrong button is a critical incident. So is repeatedly trying the same feature to accomplish a task. Users may draw attention to the critical incidents with their think-aloud, with comments like “why did it do that?” or “@%!@#$!” Critical incidents can also be positive, of course. You should note down these pleasant surprises too. Critical incidents give you a list of potential usability problems that you should focus on in the next round of iterative design.

|

|

Here are various ways you can record observations from a user test. Paper notes are usually best, although it may be hard to keep up. Having multiple observers taking notes helps. Audio and video recording are good for capturing the user’s think-aloud, facial expressions, and body language. Video is also helpful when you want to put observers in a separate room, watching on a closed-circuit TV. Putting the observers in a separate room has some advantages: the user feels fewer eyes on them (although the video camera is another eye that can make users more self-conscious, since it’s making a permanent record), the observers can’t misbehave, and a big TV screen means more observers can watch. On the other hand, when the observers are in a separate room, they may not pay close attention to the test. It’s happened that as soon as the user finds a usability problem, the observers start talking about how to fix that problem — and ignore the rest of the test. Having observers in the same room as the test forces them to keep quiet and pay attention. Video is also useful for retrospective testing — using the videotape to debrief the user immediately after a test. It’s easy to fast forward through the tape, stop at critical incidents, and ask the user what they were thinking, to make up for gaps in think-aloud. The problem with audio and video tape is that it generates too much data to review afterwards. A few pages of notes are much easier to scan and derive usability problems. Screen capture software offers a cheap and easy way to record a user test, producing a digital movie (e.g. AVI or MPG). It’s less obtrusive and easier to set up than a video camera, and some packages can also record an audio stream to capture the user’s think-aloud.

|